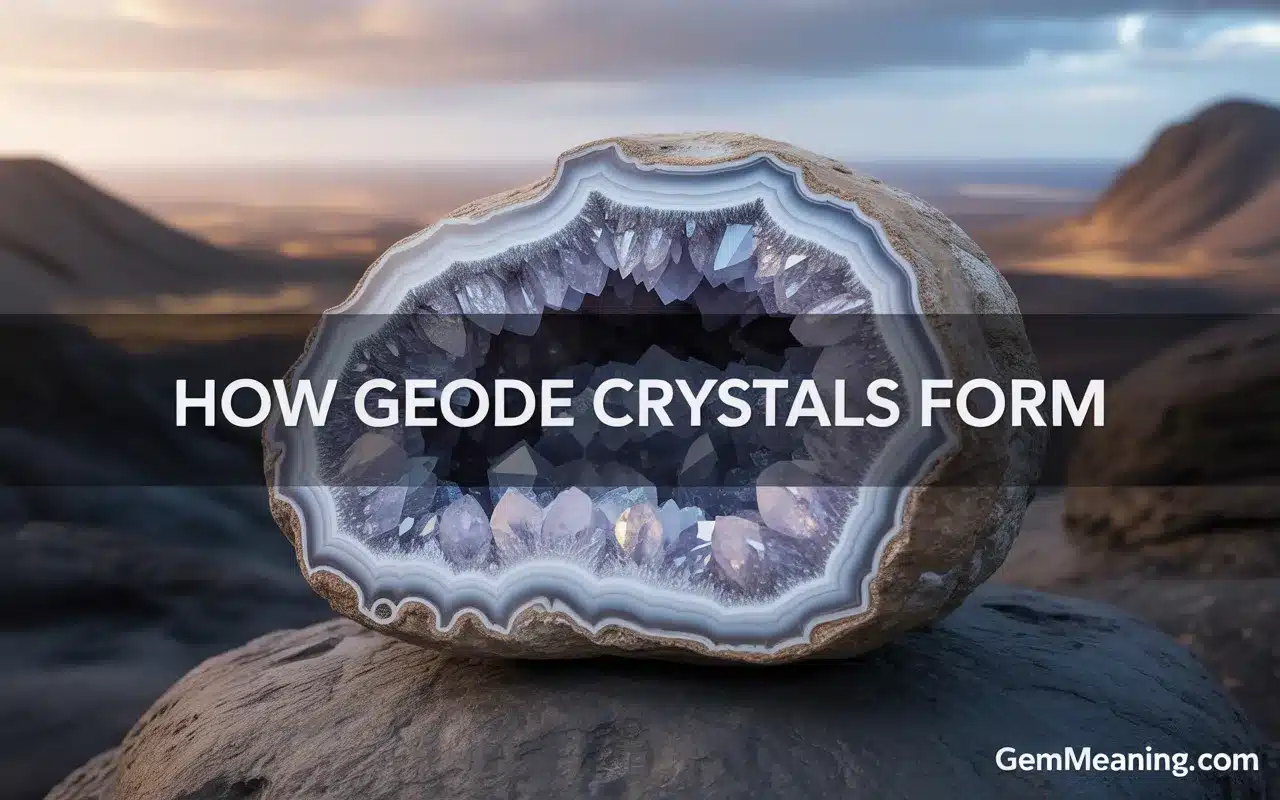

Have you ever walked along a riverbed or hiked through a dry desert landscape and kicked a dusty, round rock? To the casual observer, it looks like nothing special—just a lumpy, bumpy potato-shaped stone. But for those in the know, that humble exterior could be hiding one of nature’s most spectacular surprises. If you were to crack that rock open, you might find a hollow cavern lined with thousands of sparkling, glittering jewels.

This is the magic of finding a geode. It is the geological equivalent of a treasure chest, waiting patiently for millions of years to be opened. The contrast between the rough, ordinary outside and the dazzling, crystalline inside is what makes geode crystals so captivating to collectors and curious minds alike.

But how does this happen? How does a rock become hollow, and how do those beautiful crystals get inside without anyone putting them there? The story of how geode crystals form is a fascinating journey that involves volcanoes, ancient oceans, and a whole lot of patience.

In this guide, we are going to peel back the rocky layers and explore the secret life of geodes. We will walk through the step-by-step process of their creation, from the initial gas bubble to the final sparkle. By the end, you’ll never look at a round rock the same way again.

What Exactly Is a Geode?

Before we dive into the science of formation, let’s define what we are actually looking at. A geode is essentially a hollow rock with a secret. Technically speaking, it is a secondary geological structure that occurs within certain sedimentary and volcanic rocks.

The key feature that defines a geode is that it is hollow (or was hollow at one point). It has a durable outer wall that is more resistant to weathering than the surrounding rock bed. This is why you can often find whole geodes lying loose in the soil—the softer rock around them has eroded away, leaving the tough geode behind.

Inside this hard shell is a cavity lined with crystals growing inward toward the center. These can be tiny, glittering druzy quartz crystals or massive, chunky amethyst points. If the rock is completely filled with crystals, leaving no hollow space, it is technically called a “nodule” or a “thunderegg,” though many people still casually group them with geodes.

Geode crystals are fascinating because they are essentially miniature caves. Just as large stalactites and stalagmites form in cavern systems, these tiny crystals grow in the protected environment of the geode’s hollow center.

Step 1: Creating the Hollow Space

The first requirement for making a geode is a hole. Crystals need space to grow. If there is no empty pocket, the minerals will just fill in cracks or become part of the solid rock mass. Nature has two main ways of creating these perfect, round pockets: volcanic activity and sedimentary decay.

The Volcanic Bubble Method

Imagine a massive volcanic eruption. Lava is flowing across the landscape, molten and incredibly hot. As this lava moves, it releases dissolved gases, creating bubbles. It is very similar to the bubbles you see in a pot of boiling thick soup or carbonated soda.

As the lava begins to cool and harden into rock (like basalt or rhyolite), some of these gas bubbles get trapped. The rock hardens around the bubble, freezing that spherical shape in place forever.

This is the most common way geodes form in places like Brazil and Uruguay, which are famous for their massive Amethyst cathedrals. Those giant purple caves started as gas bubbles in ancient lava flows.

The Sedimentary Hollow Method

In the United States, particularly in the Midwest, geodes often form in sedimentary rock like limestone. This process is a little different. Instead of a gas bubble, the hollow space usually starts as something organic.

Millions of years ago, when the area was covered by shallow seas, organic materials like tree roots, shells, corals, or even animal burrows were buried in the mud and sediment. Over time, the sediment hardened into stone.

Groundwater then seeped through the rock and dissolved the organic material, leaving a hollow void behind. Sometimes, the hollow space is created when fresh water dissolves nodules of anhydrite or gypsum that were previously deposited in the rock. Either way, the result is the same: an empty room waiting to be decorated.

Step 2: The Hardening of the Shell

Once the hollow space exists, it needs to be protected. If the rock around it is too soft, the hole might collapse or fill up with mud. For a geode to form, a hard outer shell or “rind” must develop.

This rind is typically made of a tough silicate material, often Chalcedony (a type of microcrystalline quartz). As mineral-rich water begins to permeate the rock, the silica tends to precipitate, or harden, on the outer edges of the cavity first.

This creates a barrier that separates the inside of the geode from the surrounding bedrock. This shell is crucial because it acts like a skin. It is harder than the host rock, which allows the geode to survive intact even after the host rock erodes away millions of years later.

If you pick up a rough geode, you are touching this outer rind. It is often bumpy and looks a bit like a cauliflower head. This texture is the result of the silica hardening against the rough surface of the original rock cavity.

Step 3: The Mineral Infiltration

Now we have a hardened shell with an empty space inside. But how do the geode crystals get in there? The answer lies in water—specifically, groundwater that is rich in dissolved minerals.

Even though the outer shell of the geode seems solid to us, it is actually porous on a microscopic level. It acts like a very slow filter. Groundwater, carrying ingredients like silica, calcium carbonate, and other trace elements, seeps through the pores of the rock and passes through the geode’s outer shell.

Think of it like a very slow drip coffee filter. The water passes through, but it leaves something behind. The water enters the hollow cavity, and the chemical environment inside changes.

Changes in temperature, pressure, or pH levels inside the cavity cause the minerals dissolved in the water to “precipitate” out. This means they turn from a liquid solution back into a solid form. These tiny solid particles attach themselves to the inner walls of the shell.

This process is incredibly slow. We aren’t talking about days or weeks; we are talking about thousands to millions of years. It requires a stable geological environment where mineral-rich water can flow consistently for eons.

Step 4: Layer by Layer Growth

The formation of geode crystals is not a one-time event. It happens in waves or cycles, often creating distinct layers that tell the history of the stone.

The First Layers

Usually, the first minerals to deposit on the inner walls are varieties of microcrystalline quartz, like Agate or Chalcedony. Because these form relatively quickly (in geological terms), they don’t develop visible crystal points. Instead, they form smooth, banded layers lining the cavity.

This is why many geodes have a ring of white, grey, or blue agate surrounding the sparkling crystals in the center. It serves as the foundation for the larger crystals to grow on.

Growing the Points

As time goes on, the conditions might stabilize, allowing larger crystals to grow. The minerals begin to build upon each other, atom by atom, in a repeating geometric pattern.

The crystals grow inward from the walls, pointing toward the empty center. Because they are growing into an open space, they have the freedom to form perfect, sharp terminations (points). This is rare in the geological world; most crystals grow cramped against other rocks, resulting in deformed shapes.

The size of the crystals depends on the speed of growth and the concentration of minerals.

- Rapid cooling or high saturation tends to create many tiny crystals (druzy).

- Slow, steady growth allows individual crystals to grow much larger and more distinct.

The process stops when the flow of mineral-rich water is cut off, or when the geode is completely filled (becoming a nodule).

What Determines the Type of Crystals?

Not all geodes are filled with the same thing. While Quartz is the most common resident, many different minerals can form inside depending on the local geology.

Quartz Geodes

The vast majority of geode crystals are some form of Quartz (Silicon Dioxide). This is because silica is incredibly abundant in the Earth’s crust. If the water is pure silica, you get Clear Quartz.

Amethyst and Citrine

If there are trace amounts of iron in the water, and the geode is exposed to natural radiation from surrounding rocks, the quartz will turn purple, creating Amethyst. If that Amethyst is heated naturally by the earth, it can turn into golden Citrine.

Calcite Geodes

In limestone-rich areas, the water often carries calcium carbonate. This creates Calcite crystals. These look different from quartz; they are often rhombohedral (blocky) or dog-tooth shaped and are much softer than quartz.

Celestine and Barite

Some geodes contain rarer minerals like Celestine (which forms beautiful soft blue crystals) or Barite. These form when elements like strontium or barium are present in the groundwater.

The Role of Trace Elements in Color

One of the most exciting aspects of opening a geode is discovering the color inside. The exterior is almost always a dull grey or brown, offering no clue to the rainbow within.

The colors are strictly determined by impurities, known as trace elements, that were present in the groundwater during formation.

- Iron: Produces purples (Amethyst) or reds and rusty oranges (Hematite).

- Manganese: Can create pinks or blacks.

- Cobalt or Copper: Can occasionally create blues or greens, though these are rarer in standard geodes.

- Bitumen: Sometimes, organic material gets trapped inside, creating black or dark brown crystals.

Sometimes, the water chemistry changed over time. This can result in a geode that has layers of different colors—perhaps a band of blue agate, followed by a layer of white quartz, topped with a dusting of purple amethyst. These “zoned” crystals are like a timeline of the local water supply.

Where Are Geodes Found in the USA?

You don’t have to travel to exotic locations to find these geological wonders. The United States is home to some of the most famous geode beds in the world. If you live near these areas, you might even be able to go hunting for geode crystals yourself.

The Keokuk Geodes

The Midwest is famous for the “Keokuk Geode,” named after the town of Keokuk, Iowa. These geodes are found in a radius extending into Illinois and Missouri. They formed in limestone beds about 340 million years ago.

Keokuk geodes are famous for their variety. While many contain quartz, collectors have identified nearly 20 different minerals inside them, including Pyrite, Dolomite, and Kaolinite. They are essentially the “Kinder Surprise” eggs of the rock world.

Utah’s Dugway Geodes

Out in the western desert of Utah, near a place called Dugway, you can find “Dugway Geodes.” These are volcanic geodes formed in rhyolite beds. They are famous for having distinct bands of blue and pink agate inside, often with a sparkling center of clear quartz.

Kentucky, Indiana, and Tennessee

The sedimentary rock layers in these states are also prime hunting grounds. The limestone plateaus here are rich in silica and often yield beautiful, baseball-sized quartz geodes.

How Old Are Geode Crystals?

When you hold a geode, you are holding deep time in your hands. The process we just described is incredibly slow.

The volcanic rocks that host geodes in places like Brazil are often from the Cretaceous period, making them around 130 million years old. The sedimentary geodes in the American Midwest are often from the Mississippian period, making them over 300 million years old.

The crystals inside didn’t necessarily form at the same time as the rock. The hollow space formed first, and the crystallization happened later. However, the process of filling that space likely took thousands upon thousands of years of steady dripping and evaporation.

It is a humbling thought to realize that the sparkling interior of a geode has been sitting in total darkness, growing atom by atom, since before the dinosaurs walked the Earth.

The Thrill of the Hunt

There is a unique psychology to loving geodes. It is the allure of potential. Unlike a diamond or a ruby that is cut and polished by a human to look beautiful, a geode’s beauty is entirely natural and completely hidden.

When you find a geode in the wild, you are the first person—and the first being of any kind—to ever see the crystals inside. You are breaking a seal that has been closed for millions of years.

Identifying them takes a practiced eye. You look for rocks that are strangely round or cauliflower-shaped. They should feel lighter than a solid rock of the same size because of the hollow center. Shaking them sometimes reveals a rattle, indicating a loose crystal inside, though this is rare.

Cracking the Mystery: Opening a Geode

If you do find a geode, the final step in its journey is opening it. This should always be done with care to preserve the crystals inside.

While smashing it with a hammer is the most dramatic method, it often shatters the delicate crystal formations. Serious collectors prefer to use a soil pipe cutter (a tool with a chain that squeezes the rock until it pops) or a diamond saw.

Sowing a geode in half allows you to polish the flat face, highlighting the agate rings and the crystal center. Cracking it open leaves a more natural, rugged look that many people prefer.

Regardless of how it is opened, the reveal is always a moment of excitement. Will it be solid quartz? Will it be hollow with tiny sugar-like crystals? Or will it be a spectacular cavern of deep purple points?

A Miracle of Time and Water

The formation of geode crystals is a reminder that nature creates beauty in the most unexpected places. It takes a perfect storm of conditions—a gas bubble or a dissolved fossil, a hard silicate shell, mineral-rich groundwater, and eons of stability—to create these geological wonders.

The next time you see a geode sitting on a shelf, take a moment to appreciate the journey it took to get there. It started as a bubble in lava or a burrow in mud. It survived the erosion of mountains and the shifting of continents. And slowly, silently, in the dark, it built a palace of crystals inside itself.

Whether you are a serious rockhound or just someone who appreciates a pretty stone, geodes offer a tangible connection to the Earth’s ancient past. We encourage you to keep your eyes peeled next time you are near a riverbed or a limestone cliff. That dusty, round rock at your feet might just hold a sparkling secret waiting for you to discover it.