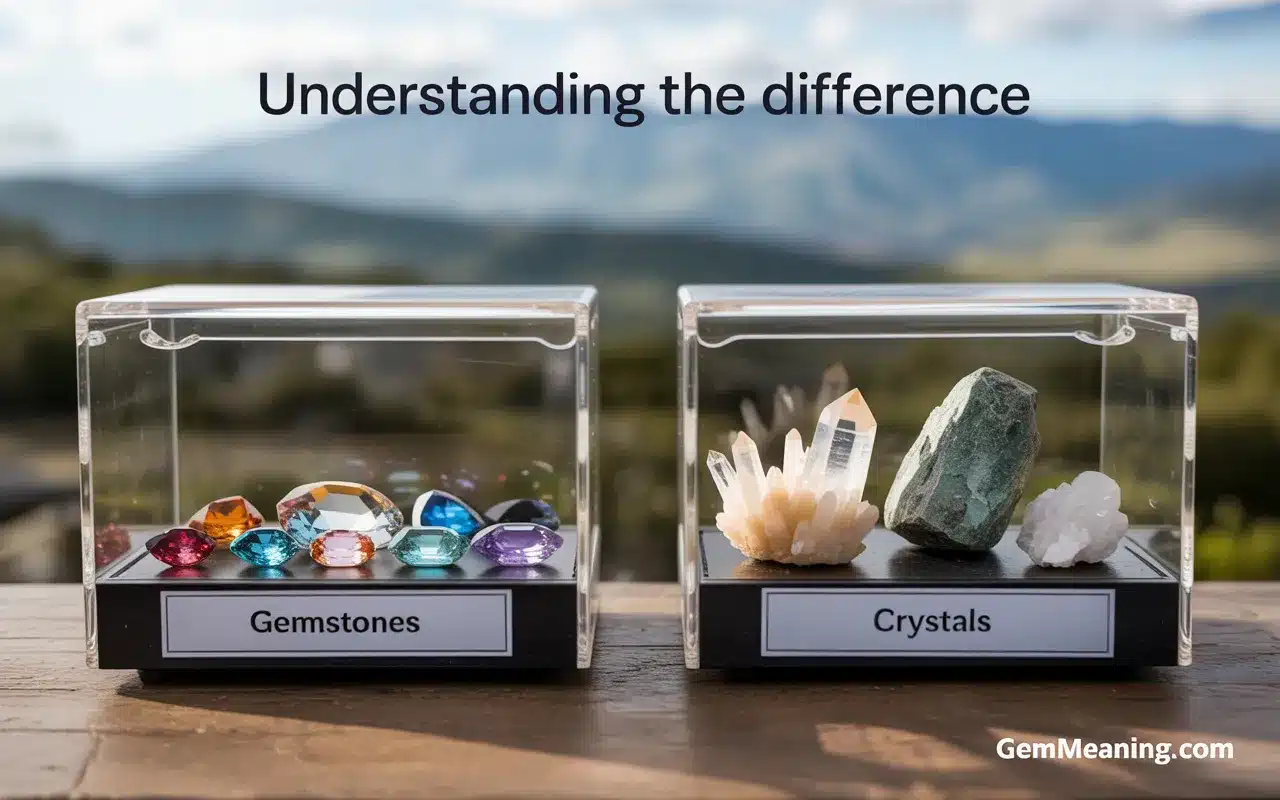

You walk into a high-end jewelry store and find yourself mesmerized by the brilliant sparkle of diamonds, emeralds, and sapphires—all carefully faceted and set in gold. Later, you browse a local metaphysical shop, drawn to the raw, earthy energy of amethyst geodes, quartz points, and tourmaline wands. You hear the words “gemstones” and “crystals” used in both places, but are they the same thing?

The line between these terms often feels blurry, leaving many collectors and enthusiasts confused. Is a ruby a crystal? Is a piece of rose quartz a gemstone? Knowing the answer is more than just trivia; it deepens your appreciation for these natural wonders and helps you understand their value and properties.

The relationship between gemstones and crystals is a fascinating story of natural formation meeting human artistry. This guide will walk you through the clear distinctions between them, explaining the scientific definition of a crystal, what elevates a crystal to the status of a gem, and how their value is determined in very different ways.

Let’s polish away the confusion and uncover the brilliant connection between these treasures of the earth.

The Scientific Foundation: What Is a Crystal?

To understand the difference between gemstones and crystals, we must start with the foundation: the crystal itself. In the world of geology, the term “crystal” has a precise scientific meaning. It’s not just a general word for a pretty, shiny rock.

A crystal is a solid material where the atoms, molecules, or ions are arranged in a highly ordered, repeating pattern. This microscopic, three-dimensional blueprint is called a crystal lattice. This internal order is the defining characteristic of a crystal and is responsible for its unique physical properties.

When a mineral has the ideal conditions—enough time, space, and stable temperatures—its atoms will naturally fall into this perfect geometric arrangement. This internal order is what creates the smooth, flat faces and sharp, consistent angles we see on the outside of a well-formed crystal. That perfect six-sided quartz point wasn’t cut that way; it grew that way, atom by atom.

Key Characteristics of a Crystal:

- It has an ordered, repeating internal atomic structure.

- It is the pure, solid form of a single mineral.

- It naturally forms geometric shapes with flat faces, known as its “crystal habit.”

- It is often transparent or translucent because light can pass through its orderly structure.

When you hold a raw tourmaline wand or a natural fluorite octahedron, you are holding a crystal in its pure, unaltered state.

The Human Distinction: What Makes a Gemstone?

Now, let’s enter the sparkling world of gemstones. Unlike the term “crystal,” the definition of a “gemstone” (or gem) is not based on geology. It is a classification based entirely on human value and appreciation.

A gemstone is a crystal that has been selected for its exceptional qualities and is then cut and polished for use in jewelry or adornment. It’s a title of honor that a crystal must earn. Very few crystals have what it takes to become a gem.

For a crystal to be considered “gem-quality,” it must excel in three specific areas. These are often called the pillars of gemology.

1. Exceptional Beauty

This is the most important quality. A gemstone must be visually stunning. Its beauty is judged on several factors:

- Color: The richness, purity, and saturation of its hue. Think of the perfect “pigeon’s blood” red of a fine ruby or the deep green of a Colombian emerald.

- Clarity: The absence of internal flaws (inclusions) or surface blemishes. A “flawless” stone is the most desirable.

- Luster: The way light reflects off the surface, giving it a brilliant shine.

- Phenomena: Special optical effects like the “fire” in a diamond, the star in a star sapphire (asterism), or the color-change in an alexandrite.

2. Significant Rarity

As with any commodity, scarcity drives up value. A crystal that is beautiful but common will not be as valuable as one that is equally beautiful but found only in a small, remote corner of the world. Tanzanite, for example, is highly prized because its only known source is a tiny mining area in Tanzania.

3. Lasting Durability

A gemstone must be tough enough to withstand the knocks and scrapes of daily wear without getting damaged. Durability is a combination of two distinct properties:

- Hardness: The resistance to scratching. This is measured on the Mohs scale from 1 (softest) to 10 (hardest). At a 10, diamond is the hardest natural substance and is ideal for rings worn every day.

- Toughness: The resistance to chipping, cracking, or breaking under impact. Jade, for example, is famous for its exceptional toughness.

When you admire a brilliant sapphire in a ring, you are looking at a crystal (of the mineral corundum) that was beautiful, rare, and durable enough to be transformed.

The Journey: How a Crystal Becomes a Gemstone

The core of the relationship between gemstones and crystals lies in this transformation. Every gemstone begins as a rough crystal mined from the earth. The process of turning that often-dull rock into a sparkling jewel is a masterful art performed by a skilled gem cutter, or lapidary.

Step 1: Assessing the Rough

The journey begins with careful examination. The lapidary studies the raw crystal to find its best color, identify internal fractures, and decide how to cut it to maximize its beauty while minimizing waste. This is the most critical stage.

Step 2: Pre-forming the Stone

The gem cutter removes flawed sections and outlines the basic shape of the final gem. This might involve splitting the crystal along a natural cleavage plane or using a diamond-tipped saw to carefully cut the rough stone.

Step 3: Faceting

This is where the magic happens. The cutter uses a machine with spinning discs (laps) coated with abrasive diamond dust to grind small, flat, polished windows onto the stone. These are called facets. The angles of these facets are precisely calculated to control how light behaves inside the stone, creating the dazzling sparkle and brilliance we associate with gems.

Step 4: Polishing

In the final step, each facet is polished with progressively finer abrasives until it achieves a perfect, mirror-like finish. This enhances the gem’s luster and brings it to life.

Through this process, a rough, earthy crystal is transformed into a fiery, brilliant gemstone, ready to be celebrated in a piece of jewelry.

The Great Divide: Are All Crystals Gems?

The simple answer is no. While all gems originate as crystals, the vast majority of crystals found on Earth will never be considered gemstones. For a crystal to make the grade, it must be of “gem quality.”

Here are the main reasons why most crystals don’t qualify:

- Poor Clarity: Most crystals are heavily included, opaque, or cloudy, preventing light from passing through beautifully.

- Subpar Color: A crystal might have a hint of color, but it may be too pale, too dark, or poorly distributed to be desirable in a gem.

- Too Soft or Fragile: Many beautiful crystals, like Fluorite (Mohs hardness 4) or Selenite (Mohs hardness 2), are simply too soft and would be easily scratched or broken if worn in jewelry.

- Too Common: Some minerals, like clear quartz, are incredibly abundant. While beautiful and highly valued for other properties, their commonness means they have little monetary value as a gemstone.

Think of it this way: all Olympic athletes are people, but very few people will ever become Olympic athletes. The same principle applies to gemstones and crystals.

Are All Gems Made from Crystals? Mostly, Yes.

The overwhelming majority of gemstones are faceted from single, crystalline minerals. Diamonds, Rubies, Sapphires, Emeralds, and Amethysts all begin their lives as well-formed crystals.

However, the world of gemology has a few interesting exceptions that are not technically crystals:

- Gems That Are Rocks: Some gems are actually rocks, which are made of multiple mineral types fused together. Lapis Lazuli, for example, is a rock composed of Lazurite, Calcite, and Pyrite.

- Amorphous Gems (Mineraloids): A few gems lack an ordered internal structure. Their atoms are jumbled randomly.

- Opal: Its unique play-of-color comes from light interacting with microscopic silica spheres, not from a crystal lattice.

- Obsidian: This is volcanic glass that cooled too quickly for atoms to organize into a crystal structure.

- Organic Gems: These are produced by living organisms and are not minerals at all.

- Pearl: Formed layer by layer inside a mollusk.

- Amber: Hardened, fossilized tree resin.

- Coral: The skeletons of tiny marine polyps.

So, while it’s a good rule of thumb that gems come from crystals, there are a handful of celebrated outliers.

A Tale of Two Values: Judging Worth

The difference between the market for gemstones and crystals is stark. They are judged by two completely different sets of standards.

How Gemstones are Valued (The 4 Cs)

The gem industry uses a standardized system to grade value, famously known as the “4 Cs” for diamonds.

- Carat: The weight of the stone (1 carat = 0.2 grams). Larger gems are exponentially rarer and more valuable.

- Color: The purity, intensity, and saturation of the stone’s hue.

- Clarity: The degree to which a gem is free from internal inclusions and external blemishes. “Flawless” is the top grade.

- Cut: The skill of the faceting, which determines the gem’s proportions, symmetry, and ability to reflect light.

How Raw Crystals are Valued

The market for raw or lightly polished crystals operates on a different, more aesthetic set of criteria.

- Form and Perfection: A perfectly formed, undamaged crystal point, a unique cluster, or a geode with large, pristine crystals is highly prized.

- Size: Larger specimens are generally more valuable.

- Inclusions (A Desirable Flaw): While inclusions are negative in a gem, they can be fascinating in a crystal. A quartz with tourmaline needles or chlorite “phantoms” inside can be more valuable than a perfectly clear one.

- Locality: The origin of a crystal matters. A specimen from a classic, depleted mine can be worth more than an identical one from a new find.

- Energy: In metaphysical circles, a crystal’s perceived energetic quality or vibration heavily influences its desirability and price.

This explains why a large, beautiful amethyst cluster might sell for a few hundred dollars, while a tiny, flawless amethyst gemstone cut from a similar crystal could command the same price or even more.

Conclusion: Two Expressions of Natural Beauty

The relationship between gemstones and crystals is one of raw potential transformed into refined perfection. A crystal is the pure, scientific form—a mineral with an ordered internal structure, just as it was born from the earth. A gemstone is what that crystal can become when it possesses exceptional quality and is touched by the masterful hand of an artisan.

You can think of a crystal as a beautiful wildflower growing in a field, while a gem is that same flower, carefully selected, pruned, and arranged into a prize-winning bouquet. One is a product of pure nature; the other is a stunning collaboration between nature and human ingenuity.

Key Takeaways:

- A crystal is a mineral with a highly ordered, repeating atomic structure.

- A gemstone is a crystal (or other natural material) that is cut and polished for use in jewelry due to its beauty, rarity, and durability.

- Nearly all gems originate as raw crystals, but only a tiny fraction of crystals are of “gem quality.”

- Crystals are valued for their natural form and unique characteristics, while gems are graded on the “4 Cs”: carat, color, clarity, and cut.

The next time you admire a sparkling ring or a raw crystal point, you’ll have a deeper understanding of its story. One is a testament to the slow, perfect geometry of geology, while the other is a celebration of that perfection, unlocked and magnified for all to see.